|

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing. |

| View of the gallery wall at Maika Carter's To connect It's Something or Call It Nothing |

In the small Project Room at the Columbus College of Art and Design Gallery, recent graduates Maika Carter is doing his first solo show, Call it something or call it nothing, until February 20th. I haven't seen much publicity for this, but I'm happy to recognize this work of questioning beauty and maturity.

The show is organized as eight

chapters of a photographic narrative. Its progression from subject to subject is clearly delineated; The content of each unit is presented in distinct, striking images, and movement from section to section feels organic. Best of all, the last chapter constitutes a synthesis of everything that came before. What did this add? Something essential and true packaged in the mundane and casual? Or an affirmation of meaning in the trivial accumulation of life?

|

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing. |

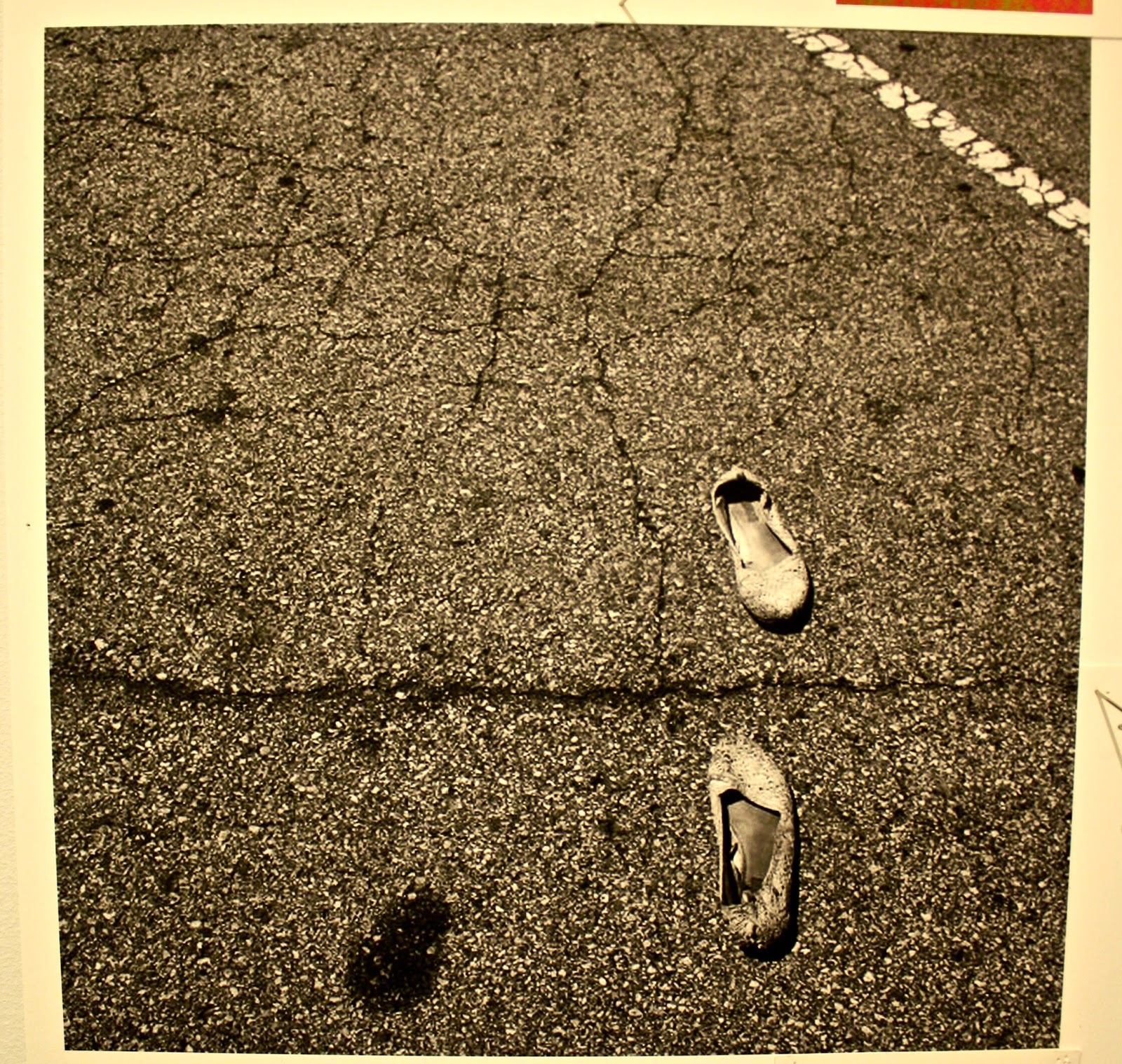

The first photographic grouping – of images large and small, tangled and pinned in thoughtful groupings on the wall – features shoes, mostly empty. The black-and-white photograph of ballet flats facing each other across a gap in the asphalt has the feel of a confident simplicity. We begin a march or a tour, but there is a question of direction and purpose from the first step. How will we fill our shoes, what is the purpose, where will we go? Carter's photographs, in black and white mixed with others in strong, saturated colors, don't suggest ambiguity to me as much as they suggest the very human condition of eagerness and determination even in the absence of a map. The images are all in bold. Does the confusion of direction between shoes indicate madness or indecision? Or simply the fact that life offers little direction?

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing. |

We walk into chapter 2 only to find ourselves in the place of the Missing, where things have disappeared or are disappearing from our sight. This is a grouping of photos that grips you not with a strong message, but with an ache of sadness that builds as you have to get closer to the many small images gathered around the larger ones. Many of the photographs on these walls are no more than 3 inches square. When Carter blurs the content, it increases the intimacy between the viewer and the image, leading to a greater emotional impact. The image of the yellow warning tape crossing the unadorned square causes, by suggestion, more sadness than I would like a lurid and graphic crime scene.

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing. Group photo including the artist. |

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it something Nothing. |

But the next section of colorful photographs move us in the way we react to a scrapbook of a large, happy family. Carter takes us to a wide array of smiling relatives and friends from multiple generations – people happy to be together, happy to be doing what they're doing, feeling special and loved. I am sure that this part of the exhibition will not leave any spectator indifferent. Carter's casual arrangement works beautifully here, where we feel the high spirits and warmth including us too. I think it's partly the scale of the images and the fact that we have to approach them up close – as if we were leafing through a scrapbook – that makes it feel so inclusive. I reacted to them not like photos of strangers, but like people whose happiness I shared. I didn't feel any barriers. The viewer is one of the company, and happy to be there as a family member of these people.

|

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing. Collection of friendship photographs. |

Are we reading an autobiography or are we a character in the artist's autobiography? Are we following an Everyman tale? The question can't help but come to mind at many points, but especially when the narrative descends from confident social well-being into a chapter of literal erasure – a morass of despondency, if you will.

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing |

Carter gives us many attractive images of humans, but with their faces or heads blurred or cut out of the frame. The smiles, the friendly connections are gone in a new environment of isolation and anonymity.

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or Call it nothing. |

The narrative continues through several other chapters that roughly alternate between presence and absence, between happily socialized security and images of an empty and adrift society.

A chapter focused on the photographer herself is particularly interesting. It would be touching if the photos weren't so bold and candid. As usual, many photos – big and small – are staged, but the viewer has to think twice to understand that the subject is the artist, so they must have been staged. Each of them has an air of total spontaneity: grimaces, dramatic poses, but with an artistic quality far beyond the photo booth. They are so natural, in fact, that they raise doubts about everything that came before. Perhaps the program really was the work of an anonymous third party.

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing. |

The set of self-portraits focuses on large real images in color and sepia, of the artist in hospital, recovering from abdominal surgery. The brightly lit hospital room with the bloody tube emanating from her belly is unnerving, except she stares at the camera as if she's talking to you, the friend close enough to be visiting. Throughout the show, you've been drawn into her world and point of view and now, here you are, paying a post-op visit, the kind you wouldn't be able to tolerate with anyone other than your best friend.

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or Call it nothing. |

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or Call it nothing. |

By the time I reached the last section of the show, everything that had come before had prepared the way for a rich consideration of the title's proposition, Call it something or call it nothing. The photographs in this area go back and forth until their messages of anxiety and hope finally intuitively merge. The artist asks herself, considering where she has been and what she has experienced so far, what is life? Something or nothing? Love or anomie? Do we invest in the future? Or do we lie down and see what happens?

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing. |

The landscape that Carter chose for this final reverie is far from dreamy, bucolic or comforting. The images are urban, spray-painted, tattooed, and seem far removed from the comforting middle-class sense of order and security that many of us associate with a life and a future that means “something.”

I'm not sure if Carter knows John Bunyon's book. The Pilgrim's Progress, but in this show I feel a connection to this tale of moral trial and resilience. The artist takes us through eight passages of pleasure, doubt and sadness. Without denying the beauty, he never stops lamenting its absence. A calm, detached air of acceptance runs throughout the show, whether we witness happy camaraderie or shots of identity loss.

I think Maika Carter's first solo show is a knockout. She shows her powers as a photographer, as a storyteller with excellent editorial sense, and as a person with wisdom and intuition that make her skills important. I, for example, will be following with great interest an artist who shows such maturity right out of the box.

| Maika Carter, from Call it something or call it nothing. |